While writing the documentation for Org-roam, it occurred to me that I have things to say that do not belong in the documentation. I wrote Org-roam because Org-mode simply didn’t have the utilities to enable the kind of note-taking workflow I wanted. I don’t want to be prescriptive about how note-taking should be done, but Org-roam is open enough to enable many note-taking styles, some of which (I feel) will be inferior to others. This post is also in part for users to understand that there are several feature requests that I may consider anti-features, such as renaming notes, having multiple org-roam directories, and having nested folder structures.

This is how I take notes. The ideas here are not my own: much of it comes from How To Take Smart Notes by Sonke Ahrens. I implore you (especially users of Org-roam) to read this through (and the book!). As usual, let me know what you think by mail.

Note-taking Is Not Just a Precursor to Writing

Notes aren’t a record of my thinking process. They are my thinking process. – Richard Feynman

In higher education, students are expected to produce papers. In fact, note-taking is not limited to students or aspiring writers: the ability to turn thoughts to writing is essential for anyone who wants to improve their learning or writing. One can imagine the process of writing to be broken down into the following steps:

- Find topic/research question

- Research/find literature

- Read and take notes

- Draw conclusions / outline text

- Write

This process may seem natural, but it is highly linear, and suggests that the process of writing begins by first deciding on a research question. But what about all those lectures and seminars you attend? Books and papers you read? Conversations with friends, colleagues, professors? Surely these ideas floating in your head, or on paper, factor into the written work somehow. Nobody starts from scratch. How do you know what’s a good research question, without relying on prior reading? How do you know what directions to explore for new ideas and insights?

Indeed, the preparation for writing begins much earlier, with note-taking! What if we follow Feynman’s advice, and make note-taking the thinking process?

Suppose you had an awesome second brain, that could surface content up to you where you wanted it. You have a bunch of unrefined ideas sitting around, thoughts you had speaking with friends, or from reading something on the web. Link them up together, and you have a paper. Instead of beginning with the research question, and going top down, we begin with the notes, and build and refine ideas from the bottom up. This also breaks writing down into small, reasonable steps (one note at a time). This is the driving principle behind the Zettelkasten method.

The primary purpose of note-taking should not be for storing ideas, but for developing them. When we take notes, we should ask: “In what context do I want to see this note again?”

A corollary for the above is that notes can go anywhere you want, they just have to surface where you want them to. This is a crucial shift in mindset. We need to be purposeful with our note-taking. Write down things that matter, refine them, file them for resurfacing later.

How do we do all these in Org-mode? This is where Org-roam comes in.

How I Take Notes

I take 2 kinds of notes: fleeting notes, and project-related notes.

Fleeting notes are notes that are taken as a reminder of what’s in my head. I take fleeting notes in my daily notes, an idea borrowed from Roam Research. This is closely related to Andy Matuschak’s Evergreen Notes.

I couple these fleeting notes with my journal, so I use org-journal to do so. Fleeting notes get refined into their own note (own file), and are removed from the daily page. These notes are given file-tags, more on this later.

Project notes are basically everything else. Here are some examples of items that get their own project note:

- a talk (e.g. Emacs Should Be Emacs Lisp - Tom Tromey)

- a book (e.g. Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are?)

- a paper (e.g. Are We Really Making Much Progress? A Worrying Analysis of Recent Neural Reco…)

- any topic or thought I’ve refined from my fleeting notes

Let’s work through an example. I picked a random link from my to-dos in my org-agenda: Ask HN: How do you learn complex, dense technical information? | Hacker News

I call org-roam-find-file, and type in the title of the note: “HN :

Learning Complex Technical Information”:

(Note the title in the backlinks buffer hasn’t updated, because I had yet to save the file)

This creates a note with a random filename (not important to my workflow) in the root org-roam folder . Throughout the note-taking process, I ask myself (I bold again to emphasise): “In what context do I want to see this note again?”

I begin to insert these contextual links to files using

org-roam-insert:

It doesn’t matter if the links don’t yet exist, Org-roam creates the

files for me. Now if I whenever I want to revisit anything about

learning, I can head to the Learning page and look at the back-links

buffer. And it seems I already have material from the Learning How To

Learn course, and an article about how to do hard things. Making these

manual connections reinforce learning.

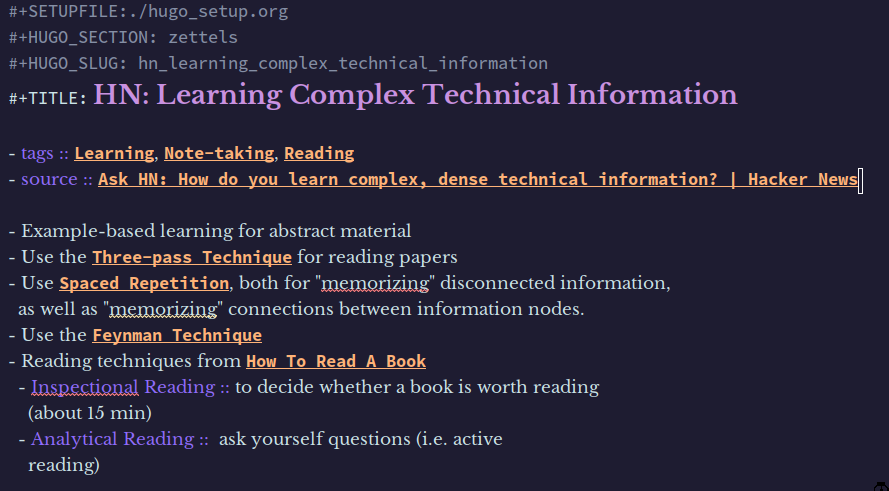

I go through the thread and start to note down things that interest me, in my own words. Again, here I create file links liberally, even though I may not yet have content in them.

For example, here I:

- see a note of the three-pass technique. I create a new link with

org-roam-insertforThree Pass Technique, and add the paper to my to-do list - I see some talk on spaced repetition. I already have a note for this, which I link to.

Here’s what the note ended up looking like. Terrible example (wasn’t really an insightful thread), but I’m in too deep now. This is for illustrative purposes only. I ended up tossing the note out, and keeping the linked articles and papers in my org-agenda.

All links are internal links to Org files within Org-roam. Doing this continuously builds up a dense network of notes. Some useful file-tags to have include file-tags from the PARA method. It doesn’t matter what file-tags you use, as long as these notes are able to present themselves when you want them to.

What Changed?

First, my notes all reside in the same folder, in a flat hierarchy. Nesting notes artificially introduces a hierarchy, which can be extremely crippling. I can rely solely on file links to make connections between notes.

Second, my notes go anywhere they want, and are generally titled based on their source. This is in contrast with putting a note under a topic (e.g. “Classical Mechanics”). Notes and ideas can belong to multiple topics: it’s much easier to just tag “topic files” (in my example, “Learning”). With this, there’s no need to think about where a note should go, and the perpetual question is (I mention yet again) “In what context do I want to see this note again?”, which is much easier and more meaningful to answer. This also means my notes almost become write-only. The notes repository can grow incredibly big, and that’s okay. Only the relevant notes surface.

How to Use These Notes

Nat Eliason produced a fantastic video showcasing how he used these notes to outline an article quickly. This is showcases essentially what I discussed earlier about putting together ideas from notes to produce a written work. If I haven’t convinced you that this note-taking style is extremely empowering, this 15 minute video will.

This article was also written in about an hour, in similar style. I first looked at all my notes from relevant tags, and clicked through their links. I simply took a couple of key points and pieced them together!

Concluding Remark

All of the above had been enabled by simply exploiting bidirectional linking to its fullest extent. What I demonstrated only scratches the surface. There are many amazing Org packages that make note-taking in Org-mode powerful (see Ecosystem - Org-Roam), for example the excellent support for LaTeX, bibtex, tables, to-do, and even literate programming.

I hope I made it clear that the note-taking technique came first, and Org-roam was built to enable that. I really encourage you to think about why you’re taking notes, and how you’d like your notes to serve you. I only recently did this introspection, and have found it life-changing.